Using Three Horizons for climate resilience

Solutions to long-term threats, such as climate change, require business leaders to think beyond the typical two or three-year planning time horizon. But, how is it possible to look further into the future when there is so much uncertainty about what the world will look like in 10 — or even 20 — years’ time?

The Three Horizons framework is one of the tools we use at Leaders’ Quest to help business leaders have better conversations about the future and move from short-term to long-term decision-making. In this article, we share the example of how Leaders’ Quest worked with the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) to facilitate a Three Horizons conversation with its member companies to explore adaptation, climate resilience and new mindsets.

What is the Three Horizons Framework?

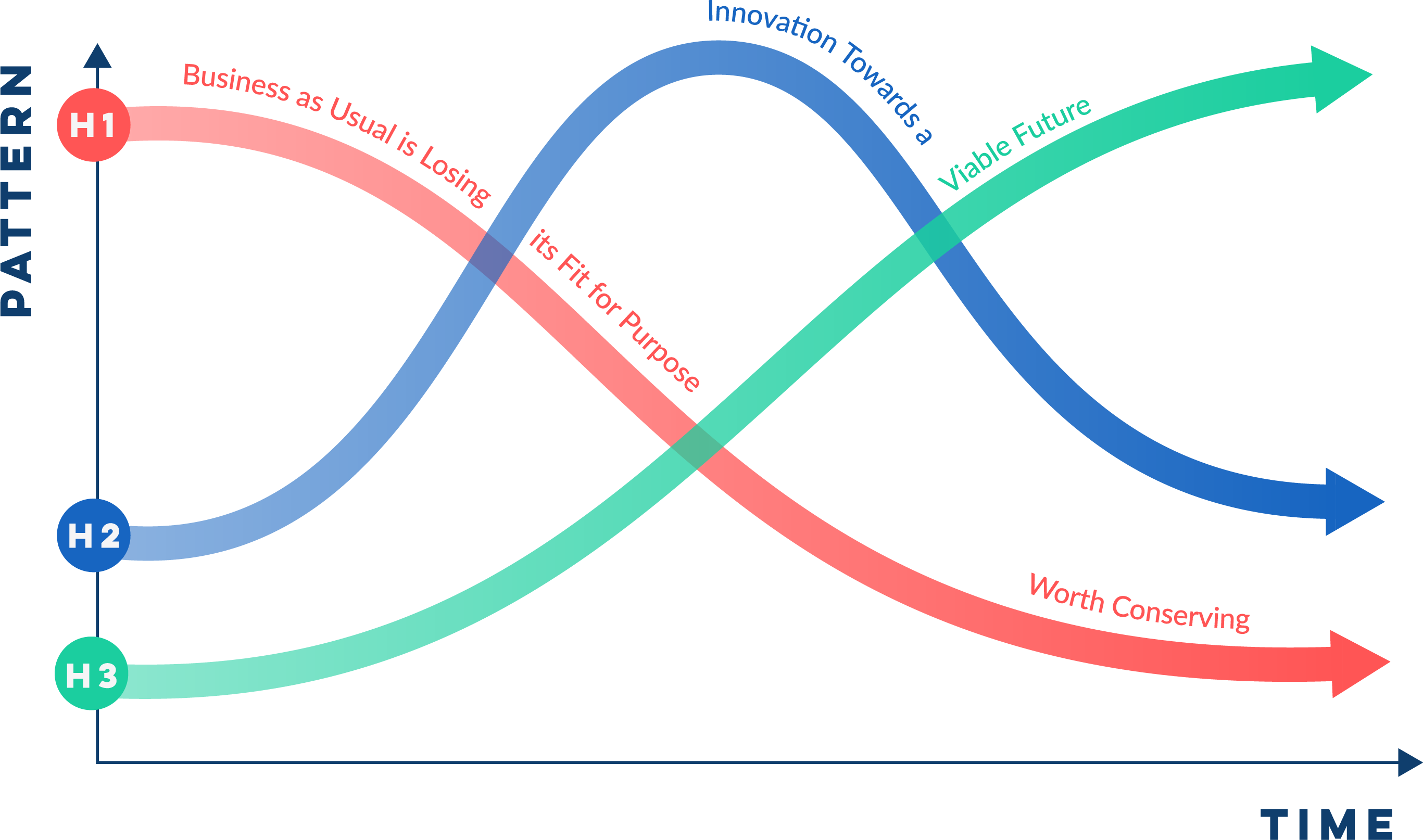

Three Horizons is a framework that helps leaders to extend the standard two-to-three-year decision-making horizon to 10, 20, or even 30 years into the future by using three perspectives (or simply say three horizons) which are:

- The first horizon is the dominant system at present, or, ‘business as usual’. We rely on these systems being stable and reliable. But as our world changes, aspects of business as usual begin to feel no longer fit for purpose.

- The second horizon is a pattern of transition activities and innovations; people trying things out in response to the ways in which the landscape is changing.

- The third horizon is the long-term successor to business as usual. It grows from activity in the present that introduces completely new ways of doing things which turn out to be much better fitted to the world that is emerging.

At Leaders’ Quest we work with the second and third horizon. In the ‘messy middle’ of the second horizon, we help leaders figure out the gap between what’s not working today and how to win in the future. In the third horizon, we unlock inspiration, mindsets and culture shifts required to create a bold ambition for the future.

How does it work?

Leaders’ Quest recently hosted a hybrid Three Horizons workshop for WBCSD and its member organisations. The topic was climate resilience, and the purpose of the workshop was to help leaders expand their thinking from mitigating against climate change (H1) towards adapting to climate change (H3).

What’s the difference between mitigation against, and adaptation to, climate change?

We need to recognize that we’re in a climate emergency — and that business needs to act urgently in providing solutions and accelerating a clean transition.

Climate mitigation can be viewed as removing harm. For instance, mitigation involves reducing emissions or enhancing sinks of greenhouse gases (GHGs), so as to limit future climate change.

Adaptation is how businesses can survive the impacts of climate change. For example, a manufacturing business may see an emerging risk of not being able to use as much water in its manufacturing process in the future and so it needs to change.

Mitigation and adaptation are not binary choices. We know that climate change is happening now–we see the effects all around us. It is crucial for businesses to set and achieve their net-zero targets and also take the leap to adapt their business models as needed.

Applying Three Horizons to climate resilience for businesses

In our workshop, it was widely accepted that businesses need a climate change mitigation strategy, however, many find it difficult to prioritise adaptation due to the uncertainty of climate risks and a lack of understanding about the likely return on investment.

We used Three Horizons to work through emerging threats to the participants’ businesses and to create pathways towards adaptation. A pathways approach allows for flexible progress towards a visionary goal and a shift in thinking that empowers leaders to create strategies that unlock long-term value creation – not just mitigation.

For example, food companies might think about shifting to seeds that require less water or acquiring climate-resistant land. Companies reliant on large amounts of data storage could consider climate-ready data centres, and companies with physical offices in coastal areas might consider partnerships with cities to build resilient infrastructure.

The impact that adaptation could have on climate resilience is sizeable: A study from the Economics of Climate Adaptation estimates that 40-70% of losses expected by 2030 as a result of climate change could be avoided through adaptation.

Helping leaders prepare for the future

Three Horizons helps teams and multi-stakeholder groups to move beyond incremental action to systemic change that supports long-term value creation.

Any leadership team can apply Three Horizons to any challenge or emerging risk.

Leaders’ Quest regularly hosts Three Horizons Facilitator Trainings. Join a growing global network of change-makers, including policymakers, researchers, business leaders, consultants, conservationists, philanthropists, activists, and community leaders who are using this transformative framework to drive positive change. Register for the trainings.